|

| 1930-2021 |

Where to begin with Broadway composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim? How about with this interview he did with another Stephen, Stephen Colbert, back in 2011? Keep in mind this isn't Colbert's current CBS late night talk show, but his earlier one on Comedy Central where he played a mock right-wing pundit. I always found the interview segment particularly intriguing because of how deftly Colbert was able to slip in actual questions that required actual answers while keeping the overall aura of parody intact. It also required that the interviewee be a good sport about the whole thing, and Sondheim was just that:

Stephen Colbert was in a Sondheim show? This I got to see. While I look for it, here's some highlights from Stephen Sondheim's life and career...

No, I'm not asking you to attend this show which was after all in March 2019, a little more than two years ago (in this age of Covid, it seems almost one hundred years ago, huh?) But it's the only picture I could find of Oscar Hammerstein II and a 16-year-old Stephen Sondheim. Hammerstein was a lyricist and librettist who had a good deal of success on Broadway in the 1920s when he teamed up with Jerome Kern to do Show Boat, a musical with an actual story and that dealt with some weighty subject matter like miscegenation and family abandonment (surprisingly, this show was produced by Florenz Ziegfeld, a man not known for social realism.) Hammerstein had a few more hits with Kern and others, but, after six flops in a row, his best days seemed past him by the start of the 1940s. Meanwhile, composer Richard Rodgers had become fed up with his longtime partner, the brilliant but alcoholic Lorenz Hart, and set about finding another lyricist. As you might have guessed, he found Hammerstein and the two set about revolutionizing the Broadway stage by specializing in the "book musical", i.e., a musical where the singing and dancing advances the plot rather than running roughshod over it. Their first big hit, Oklahoma, is a good example of this type of musical (if some cowboy sings he's having a beautiful mornin', you may be curious as to whether that's going to last into the afternoon.) As for Sondheim, born to a well-to-do family, he went to a private school where he became friends with James Hammerstein, Oscar's son. Young Stephen was already interested in musical theatre when James introduced him to his father, and now had an excellent mentor who could help him plot out his own career goals.

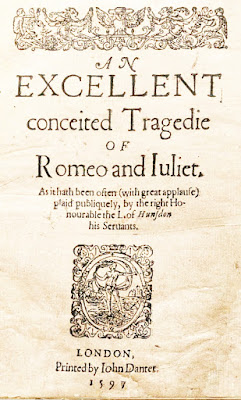

Hammerstein gave the teenager four playwriting assignments, the fourth of which, Saturday Night, was completed when Sondheim was 23. It damn near came to fruition, but the whole project fell apart when the producer died (it was finally produced in London in 1997, and has since had an off-Broadway run.) During this time Sondheim had become acquainted with the playwright Arthur Laurents (Home of the Brave.) At a party, Laurents told Sondheim about a project he, choreographer Jerome Robbins, and New York Philharmonic conductor and occasional Broadway composer Leonard Bernstein were working on that would transfer Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet from 16th century Verona to a rough neighborhood in Manhattan where white and Puerto Rican teenage gangs vied for control of the mean streets. Laurents invited Sondheim to write the lyrics. Desiring to be both a lyricist and a composer, Sondheim's first instinct was to turn Laurents down, but decided to talk it over with Oscar Hammerstein first. "Turn it down?! Are you kidding?!", Hammerstein responded. "This is Leonard-fucking-Bernstein!" Actually, Hammerstein didn't say that at all. I just felt the paragraph needed a little drama. He did tell the young Sondheim that given all the talent involved, this certainly would be a good learning experience, and so the Montagues and Capulets became...

...the Jets and the Sharks.

West Side Story premiered on Broadway in 1957, was a success, and became an even more successful movie in 1961. I've shown the following clip on this blog before, but it's my favorite number in the film, and gives you some idea how eventual Academy Award winner Rita Moreno (in a role originated on stage by Chita Rivera) was able to steal the whole movie right under a lip-syncing Natalie Wood's nose. Watch:

Is pro- and anti-Americanism really a gender thing?

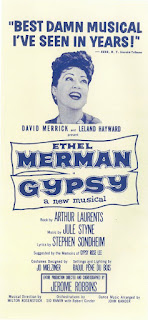

Despite West Side Story's success, Stephen Sondheim's next fifteen shows were notorious flops and he was reduced to working the ticket booth at a strip club near the airport...No, no, I'm just kidding. That's 1930s and '40s burlesque star Gypsy Rose Lee in the above photo, and that brings me to Stephen Sondheim's next major work. In 1957 Lee, whose real name was Rose Louise Hovick, wrote her autobiography, and producer David Merrick thought it would make a good musical for Ethel Merman, not as the stripper herself but her mother, the incredibly domineering Mama Rose. Merrick got the West Side Story team of Laurents, Robbins, and Sondheim together, except this time the latter insisted he write the words and music. Merman, who seems to have been every bit as domineering in real life as the characters she regularly played, insisted the novice composer not write the music. Sondheim once again went to Hammerstein for advice. "Are you kidding?! This is Ethel-fucking-Merman!" Of course, Hammerstein didn't say that, but he did counsel Sondheim that if the show was successful, it wouldn't hurt his career any. And so, the composing chores went to the more-experienced Jule Styne. Gypsy: A Musical Fable opened on Broadway in 1959 and was indeed a success. The show was as much about Mama Rose as her wardrobe-malfunctioning daughter, but we here at Shadow of a Doubt know that sex sells, so you folks are going to get treated to an actual striptease! But which striptease? In the show Mama Rose pushes her up-to-then mostly ignored daughter Louise into burlesque only after favorite daughter June (Havoc) runs off to Hollywood to become a movie star. Louise at first is very comically nervous about disrobing on stage, but gains confidence as time goes on. I wanted the before-and-after. Sandra Church originated the role of Louise on Broadway, but on YouTube there's only a sound recording of that performance. Natalie Wood played Louise in the 1962 movie (this time in her own voice and she sounds fine) but I could only find the "after" performance. Finally, I came across this little gem which seems to have been produced only for YouTube, and stars an actress named Haley Zega. (Additional biographical detail I stumbled upon: as a six-year-old she disappeared for a couple of days in the Ozark National Forest, but fortunately was found unharmed.) Watch:

One notable difference between burlesque and latter-day strip clubs is that in the former the girls never...

...climbed up a pole and slid down. I wonder how that got started anyway. Did some enterprising strip club owner renovate an abandoned firehouse?

The Glory of Rome. Over the centuries it's been an inspiration for countless poems, novels, plays, movies, and multi-part PBS series. It's also inspired at least one musical-comedy, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. Oscar Hammerstein had died in 1960, so in 1961 or so there was so one to talk Sondheim out of insisting that he write both the words and the music, and whatever insistence he gave this time paid off. AFTHOTWTTF--even doing it with just initials tires me out--premiered on Broadway in 1962, and went on to win a Tony for best musical. Curiously, despite doing double-duty as lyricist and composer, Sondheim took home nothing. It must have been the book by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart that won over Tony voters. Zero Mostel starred on stage, and, unlike Fiddler on the Roof a few years later, got to appear in the movie version as well:

After all that, it damn well better be funny. (It was.)

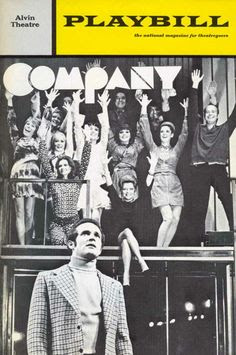

The Stephen Sondheim era really begins with the above musical that came out in 1970. Originally it was meant as a series of one-act plays by writer George Furth (also an actor, he's best known as the loyal if hapless railroad safe guard in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid) that producer Harold Prince took a look at and thought would work better as a musical. Robert has just turned 35 years old and is still single--unusual for a heterosexual male back then. Really just a fear of commitment, he takes a close look at his married friends to see if he can overcome that fear. Unfortunately, their goofy unions do little to bolster his courage. We'll let Sondheim himself tell you what's at play here:

Broadway theater has been for many years supported by upper-middle-class people with upper-middle-class problems. These people really want to escape that world when they go to the theatre, and then here we are with Company talking about how we're going to bring it right back in their faces

Those upper-middle-class people Sondheim spoke of must not have minded getting their upper-middle-class problems right back in their faces, as Company's original Broadway run lasted for 705 performances. It's also been revived many times. If you watched the video at the top of this post, you'll recall Stephen Colbert was in one of those revivals. In fact, it was three nights at the New York Philharmonic in 2011 so as you can imagine this performance had quite a bit of musical accompaniment. It also had several celebrities that one doesn't normally associate with musical theatre. In addition to Colbert, there was Neil Partrick Harris (as Robert), Martha Plimpton, and Jon Cryer. All can be found in the following clip. You'll also get to see a genuine star of music theatre, and a Broadway legend at this point, Patti LuPone (unless you're an over-40 shut-in who never watches Great Performances in which case you may know her best as Corky's mom on Life Goes On.) Watch:

If you're surprised that Colbert can act (other than as his usual right-wing pundit character) and sing, don't be. He was a theatre major at Northwestern University.

Swedish filmmaker Igmar Bergman is not someone we normally associate with Broadway musicals. Yet his 1955 movie Smiles of a Summer Night served as the basis for Sondheim's 1973 Broadway hit A Little Night Music, which introduced what is arguably his best-known song as a lyricist and composer, "Send in the Clowns", sung here by original cast member Glynis Johns (still with us at age 98, though this particular clip is from decades ago):

I get a lot of letters over the years asking what the title means and what the song's about; I never thought it would be in any way esoteric. I wanted to use theatrical imagery in the song, because she's an actress, but it's not supposed to be a circus [...] [I]t's a theater reference meaning "if the show isn't going well, let's send in the clowns"; in other words, "let's do the jokes." I always want to know, when I'm writing a song, what the end is going to be, so "Send in the Clowns" didn't settle in until I got the notion, "Don't bother, they're here", which means that "We are the fools."

--Stephen Sondheim

No wonder he's sad. All these years he thought that song was about him.

You long-haired freak! Isn't about time you went to a barber?

Sweeny Todd, a barber who kills people and then has a Mrs. Lovett serve them up to unsuspecting consumers as meat pies, first appeared on newsstands in 1840's London as a character in the anonymously written story "A String of Pearls" that was serialized in The People's Periodical and Family Library, a "penny dreadful", which were to Victorians what slasher films were to moviegoers in the 1980s. I myself haven't read this story, but I understand that it doesn't explain or expect readers to care about what motivates the murderous Todd any more than a Friday the 13th movie expects an audience member to care whether it gets hot under Jason Voorhees' hockey mask. Some 120 years after "A String of Pearls" appeared on the printed page, and after it was adopted for the stage many times with no other goal in mind than to scare the hell out of audiences, an Englishman named Christopher Boyd wrote a play in which he attempted to come up with a motive for Sweeny Todd and make him a somewhat sympathetic character. Sweeny has been jailed for a crime he didn't commit, and now wants to take it out on all humanity. Don't you feel sorry for him now? I don't know if Stephen Sondheim did, but he saw Boyd's play and thought it would make a nifty musical. He brought the idea to producer Harold Prince who saw in it a metaphor for the dehumanization brought on by the Industrial Revolution. As a late product of that Industrial Revolution who occasionally feels dehumanized (though I rarely do anything about it other than work on this blog), I find Prince's vision kind of compelling. However, I should warn the unsuspecting Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, or Alezandria Ocasio-Cortez voter that a scene like the one here featuring Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury, both from the original 1979 Broadway production--well, this ain't no Michael Moore movie:

Murder, She Sang.

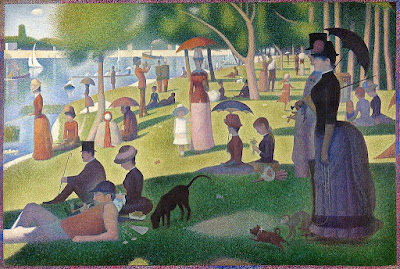

In 1985's Sunday in the Park with George, Sondheim returned to the 19th century, but a seemingly more pleasant, pastoral 19th century. George is Georges Seurat, the French post-impressionist painter who pioneered a style referred to a pointillism. Above is his most famous painting in that style, 1884's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. While pointillism was obviously abstract in nature--I've never met anybody in real life composed entirely of dots--Seurat relied on human models just as much as any Dutch Master or Rennaissance painter. In this clip, another genuine star of musical theatre (and veteran of many a Sondheim show) Bernadette Peters lets us know what it's like to be one of Seurat's models. Mandy Patinkan plays a preoccupied Seurat. Watch:

Somebody is suffering for somebody's art.

Meet Wilhelm and Jacob, 19th century German intellectuals, best known today for collecting folk stories told by non-intellectual German peasants, and then (after embellishing them a bit) publishing these stories in a series of books. You may be familiar with some of these stories: "Little Red Riding Hood" "Cinderella" "Rapunzel" and "Jack in the Beanstalk" Perhaps your parents read you these stories as a child. Perhaps you read these stories to your children. Of course, we now call such stories fairy tales. Contrary to popular belief, none of Wilhelm's and Jacob's stories ended with the phrase "and they lived happily ever after", but that was the general idea. Once they stories were over, they were over. It took until 1986, over 170 years after these stories were first published, for Stephen Sondheim and librettist James Lapine to come up with a sequel.

Without giving away multiple endings, these characters tend to live crappily ever after--if they're allowed to live at all. And they find that supposedly good and noble deeds can have unintended consequences. Such as when you kill a giant, you may make a widow out of the giantess--one pissed-off widow. Maureen McGovern may have summed up this show's central message best when she sang, "There's got to be a morning after...." But Sondheim didn't write that song. So I'll give you one that he did write. And since an encore is kind of like a sequel, let's bring back Bernadette:

Uh...How about at least letting her live aesthetically ever after?

Bernadette's memory is a bit faulty here. She in fact did sing it in the show, but only a snippet as part of the finale with the whole cast singing along with her. The song as a whole was sung by actors playing Little Red Riding Hood, Cinderella, Jack the Giant Killer, and a baker who gets to meet all these famous characters. I tried looking for a clip of that, but to be honest, quickly gave up the search once I stumbled upon Bernadette's version. Call it witchcraft.

Given the parodic Stephen Colbert interview at the top of this post, you'd be forgiven if you thought a musical about assassinations was part of the joke. But it's not. There really was such a musical, Assassins, which premiered off-Broadway in 1990, and made it to the Great White Way in 2004, stopping off at London's West End in-between. The whole motley crew of presidential killers are here: John Wilkes Booth (whom we all know killed Lincoln), Charles Guiteau (whom we all may not know killed Garfield), Leon Czolgosz (McKinley), and Lee Harvey Oswald (JFK). But it doesn't stop there. Seven or eight years ago on this blog I showed a video of an editorial that TV newsman Edwin Newman gave the day Kennedy was assassinated, in which he very calmly, almost wryly, stated that if someone was determined to take out a president, at some personal risk to themselves, they had a good chance of doing so. Well, I don't know if their determination level wasn't up to snuff or what, but the fact is the would-be presidential killers slightly outnumber the successful ones, and they're represented here as well: Giuseppe Zangara (FDR), Samuel Byck (who tried but failed to hijack a plane, hoping to crash it into the Nixon White House), Squeaky Fromme (Ford), Sara Jane Moore (Ford again, just seventeen days after Fromme's attempt), and John Hinckley Jr. (Reagan). The following clip is from a San Diego production of the show:

We're always told they're loners, but look how well they work as an ensemble

Other pursuits.

In recent years Stephen Sondheim has increasingly been referred to as God by Broadway aficionados, and that almost led me to title this post "God is Dead", but I was told a German philosopher already owns the rights to that phrase. Sondheim was just a man, after all, and one whose songs often dealt with his fellow mortals falls from grace, or their failed attempts to achieve grace, usually in a non-judgmental manner. It's his effect on the theatre that's been divine. There had been others, most notably his old mentor Oscar Hammerstein II, but it was Sondheim more than anyone else who proved that a musical play can be every bit as profound and insightful as any non-musical play, or any literary novel. An American Original, his works will continue to be regularly produced for some time to come (a revival of Assassins has opened on Broadway--it got a good review in the latest issue of The New Yorker--and Steven Spielberg's remake of West Side Story hits the movie theaters next week.) And I don't know that there's anyone currently around to take his place (Andrew Lloyd Webber? He would have done so by now.) Stephen Sondheim may not have been omniscient, but in the world of musical theatre, he remains omnipresent.

.

No comments:

Post a Comment

In order to keep the hucksters, humbugs, scoundrels, psychos, morons, and last but not least, artificial intelligentsia at bay, I have decided to turn on comment moderation. On the plus side, I've gotten rid of the word verification.