...just none of them were articulate on this intellectual level...I mean, they just didn't articulate on this level.

--Jann Wenner, when asked why there are no women or persons of color in his upcoming book of interviews with rock musicians.

It was this--the radical conventionality of Rolling Stone--that was Jann Wenner's most important innovation. When he stamped the whole package with a psychedelic logo designed by poster artist Rick Griffin--the curled ligatures and looping serifs unmistakable signifiers of dope-peddling head shops on Haight-Ashbury--he instantly legitimized and mainstreamed the underground.

Wenner had never been, exactly, a revolutionary. He wanted to overthrow the establishment by becoming the establishment. The establishment, meanwhile, wanted a taste of the new fame and glamour that Rolling Stone was charting.

Pincered between disco and punk, Wenner defaulted to what did sell: Hollywood celebrities and 1960s-era rock icons of the kind he had been putting on the cover since 1967.

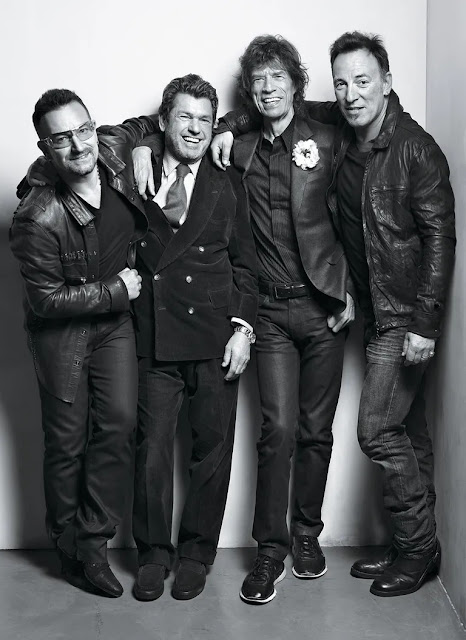

Wenner's biases and machinations--his success--had made him the gatekeeper of the history of rock and roll. And the next step was to build an institution out of it--literally, an edifice--over which he could preside...he was fashioning himself into the architect of rock's shining city on the hill: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

It was a man’s magazine, though women read it; it was a white magazine, though African Americans were fetishized in it.

--Joe Hagan, Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner and Rolling Stone Magazine

In the future the pantheon will be decentralized.

--Richard Brody