Alexander Graham Bell. Invented the telephone 90 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

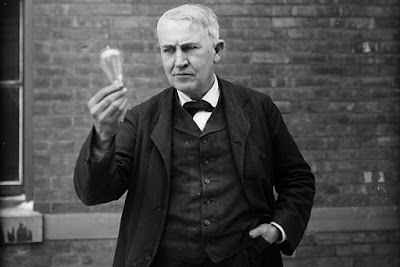

Thomas Edison. Invented the incandescent light bulb 87 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

Orville and Wilbur Wright. Invented the airplane 63 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

Charlie Chaplin. Produced, directed, wrote, and starred in the motion picture Modern Times 30 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

Speaking of motion pictures, here's an early ad for the first one based on Star Trek, an ad that was quickly rescinded. Note that it says "23rd century". The original series didn't necessarily take place in the 23rd century. Nor did it necessarily NOT not take place in the 23rd century. The TV show never exactly said when it took place, you were supposed to just assume "the future", that's all. The series hinted at times, but those hints were contradictory. In the time travel episode "Tomorrow is Yesterday", a 1967 Air Force Lieutenant, believing him to be a spy, threatens to lock Kirk up for 200 years, to which the starship captain replies, "That ought to be about right." Doing the math, that also ought to be the 22nd, and not the 23rd, century. In "The Squire of Gothos", the title alien, unaware the time it takes light to travel in space, believes Earth is still in the late 18th-early 19th century, or "900 hundred years past" according to Kirk, meaning the show should then take place in the 27th century. In the 1968 best-seller The Making of Star Trek by Stephen E. Whitfield (that a show on the verge of cancellation nonetheless could inspire a best-selling book demonstrates the cult-like following the series had during its original run) Gene Roddenberry is quoted as saying the Enterprise's five-year mission could take place as late as 1000 years in the future, or as early as 1999 (at the time three decades away, but still.) The trick, I think, is that you need it far enough in the future to account for things like interstellar space travel and molecular disassembly and reassembly ("Beam me up, Scotty") but not so far into the future that humans have evolved into floating brains (or, if you believe Kurt Vonnegut's Galapagos, dolphins.) Somehow, someone settled on the 23rd century for the first film, except that date is never actually mentioned in the film itself, just the early ad campaign for it, which the producers then backed off of. Still, 300 years in the future sounded like it might be right. The date stuck.

The Manhattan Project. 21 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

Sputnik. 9 years before Star Trek first went on the air.

23rd century or whenever, Star Trek

obviously takes place in a technologically advanced future. But to what

extent do the characters think of that era as advanced? After all, technology is

relative. Look at today. The Internet. Smart phones. GPS

tracking. It's all beginning to make an era I once thought of as

ultra-modern, and technologically advanced in its own right, the 1970s of my youth, seem vaguely quaint. Does Polaroid

still make those cameras where the picture develops right before your

eyes? Does Polaroid make anything anymore? In 1889, the 19th century seemed like such a age of marvels to Mark Twain that he was inspired to write A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court,

in which the title character introduces the steam engine, gas lights,

and the telegraph to the Middle Ages. 90 years later, Disney made a movie of

Twain's novel titled Unidentified Flying Oddball. Except by 1979, 1889 seemed a little too much like the Middle

Ages for the contrast to resonate much, so the

title character was updated to a NASA astronaut (who still may have been from Connecticut for all I know.) In between, there's the 1949

Bing Crosby version, which retained Twain's original title. Yet there's a

curious bit of updating there, too. Instead of 1889 or 1949, that movie

takes place in 1912. Why? Crosby plays an auto mechanic, a profession

largely unknown in 1889. 23 years later, however, there were 500,000

automobiles on American roads, and presumably they occasionally broke

down and you needed mechanics to repair them. 22% percent of those autos

were the increasingly affordable and increasingly popular Model T

Fords. But not nearly as affordable and popular as they would become in

1913. That year, Henry Ford had a moving assembly line installed in his

Highland Park, Michigan plant. Moving assembly lines had been around for

a while, but usually for simple things like putting sardines in cans.

Oldsmobile had tried it with cars first, but still charged wealthy

consumers through their turned-up noses, and so most Americans stuck to

horses or their own two legs. Ford, who realized you could make

more money by selling something cheap to a modest-income majority than

something expensive to a well-heeled minority, was by the mid-1910s spitting out

Model T's, displacing both the horse and the people of the world's own

two feet, and turning the entire planet into the Indianapolis 500. Writer

Aldous Huxley was so impressed--as well as alarmed and repulsed--by

Henry Ford's achievement, that he set his 1931 dystopian novel Brave New World in 632 A.F.--"After Ford". Huxley was still alive in 1961 when Disney came out with The Absent-Minded Professor.

In that decidedly non-dystopian film, the title character played by

Fred MacMurray is kidded by friends and acquaintances for "still driving that old Model T."

It seems no matter how stunning the technological development,

something soon comes along to render it trite (which reminds me, I need to replace my cell phone.)

23rd century or whenever, Star Trek

obviously takes place in a technologically advanced future. But to what

extent do the characters think of that era as advanced? After all, technology is

relative. Look at today. The Internet. Smart phones. GPS

tracking. It's all beginning to make an era I once thought of as

ultra-modern, and technologically advanced in its own right, the 1970s of my youth, seem vaguely quaint. Does Polaroid

still make those cameras where the picture develops right before your

eyes? Does Polaroid make anything anymore? In 1889, the 19th century seemed like such a age of marvels to Mark Twain that he was inspired to write A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court,

in which the title character introduces the steam engine, gas lights,

and the telegraph to the Middle Ages. 90 years later, Disney made a movie of

Twain's novel titled Unidentified Flying Oddball. Except by 1979, 1889 seemed a little too much like the Middle

Ages for the contrast to resonate much, so the

title character was updated to a NASA astronaut (who still may have been from Connecticut for all I know.) In between, there's the 1949

Bing Crosby version, which retained Twain's original title. Yet there's a

curious bit of updating there, too. Instead of 1889 or 1949, that movie

takes place in 1912. Why? Crosby plays an auto mechanic, a profession

largely unknown in 1889. 23 years later, however, there were 500,000

automobiles on American roads, and presumably they occasionally broke

down and you needed mechanics to repair them. 22% percent of those autos

were the increasingly affordable and increasingly popular Model T

Fords. But not nearly as affordable and popular as they would become in

1913. That year, Henry Ford had a moving assembly line installed in his

Highland Park, Michigan plant. Moving assembly lines had been around for

a while, but usually for simple things like putting sardines in cans.

Oldsmobile had tried it with cars first, but still charged wealthy

consumers through their turned-up noses, and so most Americans stuck to

horses or their own two legs. Ford, who realized you could make

more money by selling something cheap to a modest-income majority than

something expensive to a well-heeled minority, was by the mid-1910s spitting out

Model T's, displacing both the horse and the people of the world's own

two feet, and turning the entire planet into the Indianapolis 500. Writer

Aldous Huxley was so impressed--as well as alarmed and repulsed--by

Henry Ford's achievement, that he set his 1931 dystopian novel Brave New World in 632 A.F.--"After Ford". Huxley was still alive in 1961 when Disney came out with The Absent-Minded Professor.

In that decidedly non-dystopian film, the title character played by

Fred MacMurray is kidded by friends and acquaintances for "still driving that old Model T."

It seems no matter how stunning the technological development,

something soon comes along to render it trite (which reminds me, I need to replace my cell phone.)  Star Trek,

during its original run, examined both sides of this dichotomy. There

are times where the characters do see themselves as technologically

advanced. In "The Conscience of the King" a Shakespearean actor tells

Kirk, "Here you stand, the perfect symbol of our technical society.

Mechanized, electronicised, and not very human. You've done away with

humanity, the striving of man to achieve greatness through his own

resources." In "Errand of Mercy" Kirk himself says "We think of ourselves as the most powerful beings in the universe..." There are even Luddites in the future. In "The Way to Eden" Spock explains the goals of Dr. Sevrin and his followers: "There are many who are uncomfortable with what we have created. It

is almost a biological rebellion--a profound revulsion against the

planned communities, the programming, the sterilized, artfully balanced

atmospheres. They hunger for an Eden--where spring comes." Yet

there's also a surprising number of episodes where Kirk and co. encounter

societies that are even more technologically advanced, or else they've

given themselves over to technology to such an extent they make the crew

of the Enterprise look Amish, almost always to ill effect. In "Return

of the Archons" and "The Apple" computers set themselves up as gods to intellectually-stunted populations. In "A Taste of Armageddon" two planets wage a 500-year war via computer simulation, but the casualties are

real. The title contraption in "The Doomsday Machine" munches on

planets. As for "Mudd's Planet", a bunch of stubborn androids rule

there. A scientist programs his personality into "The Ultimate Computer"

and people die as a result. Some personality. A spaceship posing as a

planet is set to collide into the real thing in "For the World is Hollow

and I Have Touched the Sky". In all of these episodes, the

technological evil is defeated, and the crew of the Enterprise returns

to their normal lives of interstellar travel and molecule-dispersing

transporters. Now with this new film version of Star Trek, ultra-modern 1970s special

effects would be put to use in telling yet another story about advanced

technology. Whether this advanced technology was evil or not would all depend on who, or what,

was asking the question.

Star Trek,

during its original run, examined both sides of this dichotomy. There

are times where the characters do see themselves as technologically

advanced. In "The Conscience of the King" a Shakespearean actor tells

Kirk, "Here you stand, the perfect symbol of our technical society.

Mechanized, electronicised, and not very human. You've done away with

humanity, the striving of man to achieve greatness through his own

resources." In "Errand of Mercy" Kirk himself says "We think of ourselves as the most powerful beings in the universe..." There are even Luddites in the future. In "The Way to Eden" Spock explains the goals of Dr. Sevrin and his followers: "There are many who are uncomfortable with what we have created. It

is almost a biological rebellion--a profound revulsion against the

planned communities, the programming, the sterilized, artfully balanced

atmospheres. They hunger for an Eden--where spring comes." Yet

there's also a surprising number of episodes where Kirk and co. encounter

societies that are even more technologically advanced, or else they've

given themselves over to technology to such an extent they make the crew

of the Enterprise look Amish, almost always to ill effect. In "Return

of the Archons" and "The Apple" computers set themselves up as gods to intellectually-stunted populations. In "A Taste of Armageddon" two planets wage a 500-year war via computer simulation, but the casualties are

real. The title contraption in "The Doomsday Machine" munches on

planets. As for "Mudd's Planet", a bunch of stubborn androids rule

there. A scientist programs his personality into "The Ultimate Computer"

and people die as a result. Some personality. A spaceship posing as a

planet is set to collide into the real thing in "For the World is Hollow

and I Have Touched the Sky". In all of these episodes, the

technological evil is defeated, and the crew of the Enterprise returns

to their normal lives of interstellar travel and molecule-dispersing

transporters. Now with this new film version of Star Trek, ultra-modern 1970s special

effects would be put to use in telling yet another story about advanced

technology. Whether this advanced technology was evil or not would all depend on who, or what,

was asking the question.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

(1979) A giant space cloud destroys three Klingon warships, but not

before we get to see the Federation's longtime foes with a new cool

backbone-leading-to-top-of-the-nose appearance (in the original series

they merely had bushy eyebrows and swarthy complexions.) The cloud is

now headed for Earth, and Admiral Kirk, stuck in a desk job for the last

couple of years, uses the existential threat as an excuse to get back

in the Captain's chair of a newly re-fitted Enterprise, putting him at

odds with the new captain, but now First Officer Willard Decker

(the son of a character who appeared in the original series episode "The

Doomsday Machine".) Scotty, Uhura, Sulu, Chekov (now weapons officer),

Rand (now a transporter chief) and Chapel (now a doctor) are still part

of the crew, but McCoy and Spock have apparently left Starfleet. Kirk

has the former (briefly seen with a beard) recommissioned and dragooned

back to the Enterprise quite against his will. As for the latter, he's

back on Vulcan undergoing a ritual to purge all his emotions when he

senses the presence of the space cloud and decides to put the

expurgation on hold, once again returning to his old ship as Science

Officer, though he's even more aloof than before. And so the Enterprise

takes off to battle, or at least reason, with the cloud. Problem is,

there's still a few bugs in the refitted Enterprise, as witnessed by a

couple of crew members who melt or something while being beamed aboard. A

second problem is Kirk's not familiar with all the changes done to his

ship, and in fact almost gets everybody killed a couple times, saved

only by Decker, who's then reprimanded by the new/old captain for "competing"

with him. The Kirk-Decker feud basically falls in the background once

the Enterprise catches up with the space cloud. Or the space cloud

catches up with the Enterprise. A shiny probe appears on the bridge and

abducts the ship's new navigator (and Decker's old flame) Ilia. She's either

replaced, combined with, or turned into the probe who wants to know why there are so

many "carbon units infesting" the Enterprise. Spock

notices the probe is partial to Decker, suggesting it has retained some

of Ilia's memories. Decker is assigned the task of wooing Ilia all over

again, but to no avail. All she cares about is finding her "Creator"

and feels the carbon forms on the Enterprise, and eventually on Earth

as well are just getting in the way. Spock has some success

mind-melding with the cloud, finding out it has a name: V'Ger. Quite on his own, Spock decides to

get a closer look at this cloud. He nerve-pinches a guard, suits up, and spacewalks

right into the heart of the thing, where he sees hundreds of planets and

stars and the like. Upon his return, and after resting up in sick bay

as the experience almost killed him, Spock reveals that in the heart of the

cloud is a 20th century Voyager probe that's been missing for 300 years (NASA really did send up several spacecraft with that name though this particular one is fictional.) Seems it

disappeared into a black hole only to end up on some planet populated by

living machines. Sent back out to learn all there is to learn, it now

wants to find its creator. V'Ger shows its bias by refusing

to believe that the creator might be a carbon unit (the good people at

NASA) rather than a machine. Unfortunately, not only is there no longer a

NASA in the 23rd-or-whenever century, all of the computer codes that could be used

to contact V'Ger have disappeared, too. The Earth defenses have now been

rendered useless by the up-fitted probe, every man, woman, and child (as well as plants and

animals) in mortal danger. Somehow this problem is solved when

Decker--through one helluva whiz-bang light show--merges with the

Ilia/probe, and they jointly merge with V'Ger, hurtling all three into

some other dimension. Everything now back to normal, Scotty offers to return

Spock to Vulcan, but he's gotten such an epiphany from the whole

experience (even shedding tears at one point) that he's decided

there's nothing left for him there.

Star Trek: The Motion Picture

(1979) A giant space cloud destroys three Klingon warships, but not

before we get to see the Federation's longtime foes with a new cool

backbone-leading-to-top-of-the-nose appearance (in the original series

they merely had bushy eyebrows and swarthy complexions.) The cloud is

now headed for Earth, and Admiral Kirk, stuck in a desk job for the last

couple of years, uses the existential threat as an excuse to get back

in the Captain's chair of a newly re-fitted Enterprise, putting him at

odds with the new captain, but now First Officer Willard Decker

(the son of a character who appeared in the original series episode "The

Doomsday Machine".) Scotty, Uhura, Sulu, Chekov (now weapons officer),

Rand (now a transporter chief) and Chapel (now a doctor) are still part

of the crew, but McCoy and Spock have apparently left Starfleet. Kirk

has the former (briefly seen with a beard) recommissioned and dragooned

back to the Enterprise quite against his will. As for the latter, he's

back on Vulcan undergoing a ritual to purge all his emotions when he

senses the presence of the space cloud and decides to put the

expurgation on hold, once again returning to his old ship as Science

Officer, though he's even more aloof than before. And so the Enterprise

takes off to battle, or at least reason, with the cloud. Problem is,

there's still a few bugs in the refitted Enterprise, as witnessed by a

couple of crew members who melt or something while being beamed aboard. A

second problem is Kirk's not familiar with all the changes done to his

ship, and in fact almost gets everybody killed a couple times, saved

only by Decker, who's then reprimanded by the new/old captain for "competing"

with him. The Kirk-Decker feud basically falls in the background once

the Enterprise catches up with the space cloud. Or the space cloud

catches up with the Enterprise. A shiny probe appears on the bridge and

abducts the ship's new navigator (and Decker's old flame) Ilia. She's either

replaced, combined with, or turned into the probe who wants to know why there are so

many "carbon units infesting" the Enterprise. Spock

notices the probe is partial to Decker, suggesting it has retained some

of Ilia's memories. Decker is assigned the task of wooing Ilia all over

again, but to no avail. All she cares about is finding her "Creator"

and feels the carbon forms on the Enterprise, and eventually on Earth

as well are just getting in the way. Spock has some success

mind-melding with the cloud, finding out it has a name: V'Ger. Quite on his own, Spock decides to

get a closer look at this cloud. He nerve-pinches a guard, suits up, and spacewalks

right into the heart of the thing, where he sees hundreds of planets and

stars and the like. Upon his return, and after resting up in sick bay

as the experience almost killed him, Spock reveals that in the heart of the

cloud is a 20th century Voyager probe that's been missing for 300 years (NASA really did send up several spacecraft with that name though this particular one is fictional.) Seems it

disappeared into a black hole only to end up on some planet populated by

living machines. Sent back out to learn all there is to learn, it now

wants to find its creator. V'Ger shows its bias by refusing

to believe that the creator might be a carbon unit (the good people at

NASA) rather than a machine. Unfortunately, not only is there no longer a

NASA in the 23rd-or-whenever century, all of the computer codes that could be used

to contact V'Ger have disappeared, too. The Earth defenses have now been

rendered useless by the up-fitted probe, every man, woman, and child (as well as plants and

animals) in mortal danger. Somehow this problem is solved when

Decker--through one helluva whiz-bang light show--merges with the

Ilia/probe, and they jointly merge with V'Ger, hurtling all three into

some other dimension. Everything now back to normal, Scotty offers to return

Spock to Vulcan, but he's gotten such an epiphany from the whole

experience (even shedding tears at one point) that he's decided

there's nothing left for him there.

A

nice try. That's my opinion of this film. Costing $44 million dollars

(adjusted for inflation, today it would be...well, I have no idea but

even not adjusted for inflation I could still buy a lot of pizzas with it)

this film should at the very least be nice. Robert Wise, who had his biggest hit was The Sound of Music but whose science fiction cred rests with the 1951 classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, directed this in an impressionistic style that enhances the sense of wonder we've come to expect from Star Trek. The special effects are more than nice, they're FANTASTIC, but that may be part of the problem. Trek has

never been solely about the wonder (it couldn't be, given the original

series shoestring budget) but also the people doing the wondering.

Everything is so grand (including a San Francisco of the future) that

it's hard not to blame V'Ger for wanting to eliminate the carbon units.

They get in the way of the sheer spectacle. Except for the antiseptic

interiors of the Enterprise. The whole ship now looks like Sick Bay. The

new uniforms are either light blue or light beige, darker, gaudier hues

having been banned. The old series, for all its high-mindedness, had at

least a flirting relationship with the pulpier forms of sci-fi. Whereas

this new version has sworn off trolling for tramps in a trailer park,

married a nice girl with impeccable (if a tad austere) taste in fashion

and furniture, and moved to the suburbs.

A

nice try. That's my opinion of this film. Costing $44 million dollars

(adjusted for inflation, today it would be...well, I have no idea but

even not adjusted for inflation I could still buy a lot of pizzas with it)

this film should at the very least be nice. Robert Wise, who had his biggest hit was The Sound of Music but whose science fiction cred rests with the 1951 classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, directed this in an impressionistic style that enhances the sense of wonder we've come to expect from Star Trek. The special effects are more than nice, they're FANTASTIC, but that may be part of the problem. Trek has

never been solely about the wonder (it couldn't be, given the original

series shoestring budget) but also the people doing the wondering.

Everything is so grand (including a San Francisco of the future) that

it's hard not to blame V'Ger for wanting to eliminate the carbon units.

They get in the way of the sheer spectacle. Except for the antiseptic

interiors of the Enterprise. The whole ship now looks like Sick Bay. The

new uniforms are either light blue or light beige, darker, gaudier hues

having been banned. The old series, for all its high-mindedness, had at

least a flirting relationship with the pulpier forms of sci-fi. Whereas

this new version has sworn off trolling for tramps in a trailer park,

married a nice girl with impeccable (if a tad austere) taste in fashion

and furniture, and moved to the suburbs.

Even if they're overwhelmed at times by all the pyrotechnics, the actors all do good work. As a newcomer to Star Trek, Stephen

Collins sometimes seems unsure exactly how he fits it with this crowd,

but then that's pretty much the whole point of his character, Williard Decker.

Collins is at his best in his scenes with Bollywood actress Persis

Khambatta, who's both Ilia and the probe-that-looks-like-Ilia.

She does a nice job playing two characters who occasionally are one and

the same. However, keeping with the TV show (as well as pulpier forms of

sci-fi) she's also this movie's sex symbol, but with a twist.

Beautiful, nubile, with a great pair of gams--except she's bald! For all

its highfalutin philosophy, this is the film at its most provocative.

The feminine form literally topped by something our culture considers

anything but feminine. The movie dares you to not find her attractive,

challenges you not to be turned on. The kind of erotic contrariness that

Lady Gaga knows all too well. Or Sinead O'Conner, who obviously looks more the

part. Who knows? Maybe O'Conner caught this film back in '79 and was

inspired by it. As for the cast from the TV version, they've all settled

back into their old roles as if the original series had just gone off

the air the day before. In fact, Barret, Doohan, Koenig, Nichols, and Takai, as,

respectively, Chapel, Scotty, Chekov, Uhura, and Sulu, have about as much

to do in this movie as they did in the TV show. In the first

half-season in which she appeared, Grace Lee Whitney--Janice Rand--actually did have

more to do than those other players. As James T. Kirk's incipient love

interest, she was the focal point of several early episodes. Now just

seen briefly as the frazzled transporter chief, the interest seems

never to have gotten past the incipient stage. William Shatner is good as

Kirk. His acting style is often made fun of, but I thought the fits and

starts and even the occasional sputtering of the Enterprise captain as a

not unrealistic response to the dangers he faced on a regular basis.

Being chased by a different monster every week could make anyone appear

bipolar. At least in this film Shatner has an extra hour to pace

himself. He's a more conflicted character here, with a bit of

melancholia about him in his desire to be relevant, a desire that possibly exceeds

the need for his particular brand of relevancy. All of which, of course, makes him a more sympathetic character. When Kirk tells Decker not to compete with him, we

know he's wrong (as Decker has just saved the day) yet our heart goes out to him all the same. Since he neither figures out what V'Ger is all

about nor makes the sacrifice/physical transformation that sends the space

cloud on its computer programmed way, Kirk is a surprisingly passive

figure here, though his "thataway" that ends the film signals a

determination to propel the narrative (as he noisily will in several

succeeding films.) Now, every transcendent science fiction epic

needs an Everyman. 2001: A Space Odyssey had Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea). Close Encounters of the Third Kind had Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss). Star Trek: The Motion Picture

has...Dr. Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley)! Except whereas Bowman and Neary

were in awe of the wondrous things of which they bore witness, McCoy is as always annoyed and unsettled and eager to escape from anything

that doesn't smack of the familiar. Consequently, Kelley has some of the best,

certainly the funniest lines in the movie. When, after a near-disaster,

Chekov informs him there are no casualties, McCoy replies, "Wrong, Mr. Chekov, there are casualties. My wits! As in, frightened out of!" When Spock suggests Ilia/V'Ger probe be treated as a child, McCoy's response: "Spock, this child is about to wipe out every living thing on Earth. Now, what do you suggest we do? Spank it?!" In his own cantankerous way, McCoy is even more logical than Spock.

Even if they're overwhelmed at times by all the pyrotechnics, the actors all do good work. As a newcomer to Star Trek, Stephen

Collins sometimes seems unsure exactly how he fits it with this crowd,

but then that's pretty much the whole point of his character, Williard Decker.

Collins is at his best in his scenes with Bollywood actress Persis

Khambatta, who's both Ilia and the probe-that-looks-like-Ilia.

She does a nice job playing two characters who occasionally are one and

the same. However, keeping with the TV show (as well as pulpier forms of

sci-fi) she's also this movie's sex symbol, but with a twist.

Beautiful, nubile, with a great pair of gams--except she's bald! For all

its highfalutin philosophy, this is the film at its most provocative.

The feminine form literally topped by something our culture considers

anything but feminine. The movie dares you to not find her attractive,

challenges you not to be turned on. The kind of erotic contrariness that

Lady Gaga knows all too well. Or Sinead O'Conner, who obviously looks more the

part. Who knows? Maybe O'Conner caught this film back in '79 and was

inspired by it. As for the cast from the TV version, they've all settled

back into their old roles as if the original series had just gone off

the air the day before. In fact, Barret, Doohan, Koenig, Nichols, and Takai, as,

respectively, Chapel, Scotty, Chekov, Uhura, and Sulu, have about as much

to do in this movie as they did in the TV show. In the first

half-season in which she appeared, Grace Lee Whitney--Janice Rand--actually did have

more to do than those other players. As James T. Kirk's incipient love

interest, she was the focal point of several early episodes. Now just

seen briefly as the frazzled transporter chief, the interest seems

never to have gotten past the incipient stage. William Shatner is good as

Kirk. His acting style is often made fun of, but I thought the fits and

starts and even the occasional sputtering of the Enterprise captain as a

not unrealistic response to the dangers he faced on a regular basis.

Being chased by a different monster every week could make anyone appear

bipolar. At least in this film Shatner has an extra hour to pace

himself. He's a more conflicted character here, with a bit of

melancholia about him in his desire to be relevant, a desire that possibly exceeds

the need for his particular brand of relevancy. All of which, of course, makes him a more sympathetic character. When Kirk tells Decker not to compete with him, we

know he's wrong (as Decker has just saved the day) yet our heart goes out to him all the same. Since he neither figures out what V'Ger is all

about nor makes the sacrifice/physical transformation that sends the space

cloud on its computer programmed way, Kirk is a surprisingly passive

figure here, though his "thataway" that ends the film signals a

determination to propel the narrative (as he noisily will in several

succeeding films.) Now, every transcendent science fiction epic

needs an Everyman. 2001: A Space Odyssey had Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea). Close Encounters of the Third Kind had Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss). Star Trek: The Motion Picture

has...Dr. Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley)! Except whereas Bowman and Neary

were in awe of the wondrous things of which they bore witness, McCoy is as always annoyed and unsettled and eager to escape from anything

that doesn't smack of the familiar. Consequently, Kelley has some of the best,

certainly the funniest lines in the movie. When, after a near-disaster,

Chekov informs him there are no casualties, McCoy replies, "Wrong, Mr. Chekov, there are casualties. My wits! As in, frightened out of!" When Spock suggests Ilia/V'Ger probe be treated as a child, McCoy's response: "Spock, this child is about to wipe out every living thing on Earth. Now, what do you suggest we do? Spank it?!" In his own cantankerous way, McCoy is even more logical than Spock.And what of Spock?

I think, therefore I am.

--René Descartes

One might compare the relation of the ego to the id with that between a rider and his horse. The horse provides the locomotor energy, and the rider has the prerogative of determining the goal and of guiding the movements of his powerful mount towards it. But all too often in the relations between the ego and the id we find a picture of the less ideal situation in which the rider is obliged to guide his horse in the direction in which it itself wants to go.

--Sigmund Freud

What is meant here by saying that existence precedes essence? It means first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene, and, only afterwards, defines himself. If man, as the existentialist conceives him, is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be.

--Jean-Paul Sartre.

There are times when all the world's asleep,

The questions run too deep

For such a simple man.

Won't you please, please tell me what we've learned

I know it sounds absurd

But please tell me who I am.

--Supertramp

Leonard Nimoy's performance is really at the heart of this film. I said in an earlier installment that of all the Enterprise crew members that we're aware of, Spock is the most open-minded, the most tolerant toward life-forms other than his own. The one exception is the human race, which he finds constant fault with: "Curious how often you Humans manage to obtain that which you do not want." "Your whole Earth history is made up of men seeking absolute power." At the end of "Mirror, Mirror" when asked what he thought of the parallel universe versions of Kirk, McCoy, Scotty, and Uhura, Spock replies: "...I had the opportunity to observe your counterparts here quite closely. They were brutal, savage, unprincipled, uncivilized, treacherous, in every way, splendid examples of homo sapiens, the very flower of humanity." You can argue Spock's every bit as bigoted as McCoy, except toward those who ears happen to be rounded. Remember, though, as a Vulcan he's outnumbered 7 to 1 among the Enterprise crew members we see most often. The extras and one-shot characters seem to be human, too, so it's really about 400 to 1. Spock's criticisms are really a survival tool, a way of maintaining his sense of self in what to him is an alien culture: "Doctor, I am well aware of human characteristics. I am frequently inundated by them, but I've trained myself to put up with practically everything." My theory is that the inundation finally gets to Spock. So he parts company with what he sees as a starship full of Stanley Kowalskis and returns to Vulcan to undergo "kolinahr", the expurgation (suppression?) of emotions to get that sense of self back.

Problem is,

having been inundated in another environment for the past five years, he

can now see Vulcan from the outside and recognize it for what it is: artifice. A

cultural construct. Not necessarily a bad cultural construct. Maybe the

best cultural construct around. But it's like if you go off to college

or the army (or, in his case, Starfleet) and return home, that home is

never quite the same, even if nothing's changed, because it is YOU that have

changed. Your horizons have been expanded. Spock probably could

commiserate with the three returning servicemen (actors Harold Russell,

Dana Andrews, and Fredric March) in the 1946 film The Best Years of Our

Lives. Their horizons expanded to an often horrific degree thanks to

World War II, they're met with indifference, bafflement, and impatient pleas to just "snap out of it" by the folks at home. Spock, of course, has seen his share of horrors as a Starfleet officer, but even when a particular adventure has been more "fascinating" than lethal, it could still be beyond the ken of the average non-spacefaring Vulcan, who, whenever we're allowed to glimpse one, seems more interested in paganish ritual of the meditative sort and little else. So what's a returning serviceman, be he from Earth or Vulcan, to do? Well, you can once again take leave of the place, as Dana Andrews attempts to do toward the end of TBYOOL. Or you can take to drink, Fredric March's solution. Or you can do your best to fit in. Harold Russell's personal best is marriage to his childhood sweetheart. Spock's already tried that and it didn't work out too well ("Amok Time") so he opts for kolinahr. If anyone's going to meet Spock's newly expanded horizons with indifference, it might as well be Spock himself. Bye, bye, emotions.

Problem is,

having been inundated in another environment for the past five years, he

can now see Vulcan from the outside and recognize it for what it is: artifice. A

cultural construct. Not necessarily a bad cultural construct. Maybe the

best cultural construct around. But it's like if you go off to college

or the army (or, in his case, Starfleet) and return home, that home is

never quite the same, even if nothing's changed, because it is YOU that have

changed. Your horizons have been expanded. Spock probably could

commiserate with the three returning servicemen (actors Harold Russell,

Dana Andrews, and Fredric March) in the 1946 film The Best Years of Our

Lives. Their horizons expanded to an often horrific degree thanks to

World War II, they're met with indifference, bafflement, and impatient pleas to just "snap out of it" by the folks at home. Spock, of course, has seen his share of horrors as a Starfleet officer, but even when a particular adventure has been more "fascinating" than lethal, it could still be beyond the ken of the average non-spacefaring Vulcan, who, whenever we're allowed to glimpse one, seems more interested in paganish ritual of the meditative sort and little else. So what's a returning serviceman, be he from Earth or Vulcan, to do? Well, you can once again take leave of the place, as Dana Andrews attempts to do toward the end of TBYOOL. Or you can take to drink, Fredric March's solution. Or you can do your best to fit in. Harold Russell's personal best is marriage to his childhood sweetheart. Spock's already tried that and it didn't work out too well ("Amok Time") so he opts for kolinahr. If anyone's going to meet Spock's newly expanded horizons with indifference, it might as well be Spock himself. Bye, bye, emotions. Except V'ger is hardly indifferent. Spock senses it way

out in space and the Vulcan elders don't. Think they'd be a bit

jealous of Spock's unique ability, but jealousy is an emotion and that

would be illogical. Really, though, why is Spock able to do that? Just

as the half-human, half-Vulcan is now too self-conscious to be

completely comfortable in his own homeland, apparently (as it will soon

be revealed) the half-NASA, half-alien V'Ger is going through

its own identity crises. So Spock returns to Kirk and co. Not that he's

any more comfortable doing that. He's now a returning serviceman reluctantly returned to service. Spock may be newly-aware of Vulcan as a

cultural construct, but he's always felt that way about the

Enterprise. I'm thinking here of the scene where, shortly after arriving

at his former workplace, Spock, Kirk, and McCoy adjourn to a side room

designed in Danish Modern (well, it'd be retro to those three.)

Standing erect as a flagpole, Spock's discomfort is palpable as Kirk

urges him to sit down. When he finally does, it's the most awkward

acquiescence to a request I've ever seen. McCoy, of course, is ready with

a wisecrack: "Spock, you haven't changed a bit. You're just as warm and sociable as ever." Spock, of course, has a good comeback: "Nor have you, doctor, as your continued predilection for irrelevancy demonstrates."

But, unlike every other instance, he takes no satisfaction on

getting a good one off the doctor. Indeed, it's a bit of a chore, the

comeback slowly oozing out his mouth like the last bit of ketchup out of a

bottle. Now, let's jump ahead to just after Spock's spacewalk into the

heart of V'Ger, when he ends up in Sick Bay. Clasping Kirk's hand, he says: "I saw

V'Ger's planet, a planet populated by living machines. Unbelievable

technology. V'Ger has knowledge that spans this universe. And, yet, with

all this pure logic, V'Ger is barren, cold, no mystery, no beauty. I

should have known [...] This simple feeling [clasping Kirk's hand] is beyond V'Ger's comprehension. No meaning, no hope, and, Jim, no answers. 'Is this all I am? Is there nothing more?'"

Spock is obviously dismayed by this lack of beauty and mystery and the

simple act of clasping a hand. The question is, why? The obvious answer

is that it's Spock's human half that's dismayed. And that his human half

is probably equally dismayed at the push for pure logic on his own home

planet of Vulcan. I'm sure anywhere from 3% to 10% of you folks out

there--the statistics stubbornly refuse to stay put--can probably relate to a

biological urge at odds with societal norms. No, I'm not saying that Spock is gay--he gets it on quite readily with both Leila Kalomi (Jill Ireland) in "This Side of Paradise" and Zarabeth (a scantily clad Mariette Hartley) in "All Our Yesterdays", two episodes where his emotions, and possibly his libido, get the best of him--only that his paradoxical genetic makeup could give rise to a similar set of challenges. In that respect, kolinahr can even be seen as a kind of conversion therapy. Except Spock isn't just

dismayed but surprised that there's no beauty or mystery or

simple acts of hand clasping on V'Ger's planet. And that surprise makes

me think those things indeed must exist on Spock's own home world, albeit in

muted form, furthering my belief that Vulcans are really just a bunch of poseurs (as is true of any culture, be it a New Guinea tribe, the Middle East, or

the United States of America.) Vulcans aren't machines, they just wish they

were machines. With horrifying clarity, Spock has seen just what

would happen were that wish ever to come true. That's not to say

he's now ready to embrace the violence-ridden, angst-ridden,

heartbreak-ridden Earth Human lifestyle, and, in fact, he never does (There's GOT to be some other alternative, he's probably thinking.)

Except V'ger is hardly indifferent. Spock senses it way

out in space and the Vulcan elders don't. Think they'd be a bit

jealous of Spock's unique ability, but jealousy is an emotion and that

would be illogical. Really, though, why is Spock able to do that? Just

as the half-human, half-Vulcan is now too self-conscious to be

completely comfortable in his own homeland, apparently (as it will soon

be revealed) the half-NASA, half-alien V'Ger is going through

its own identity crises. So Spock returns to Kirk and co. Not that he's

any more comfortable doing that. He's now a returning serviceman reluctantly returned to service. Spock may be newly-aware of Vulcan as a

cultural construct, but he's always felt that way about the

Enterprise. I'm thinking here of the scene where, shortly after arriving

at his former workplace, Spock, Kirk, and McCoy adjourn to a side room

designed in Danish Modern (well, it'd be retro to those three.)

Standing erect as a flagpole, Spock's discomfort is palpable as Kirk

urges him to sit down. When he finally does, it's the most awkward

acquiescence to a request I've ever seen. McCoy, of course, is ready with

a wisecrack: "Spock, you haven't changed a bit. You're just as warm and sociable as ever." Spock, of course, has a good comeback: "Nor have you, doctor, as your continued predilection for irrelevancy demonstrates."

But, unlike every other instance, he takes no satisfaction on

getting a good one off the doctor. Indeed, it's a bit of a chore, the

comeback slowly oozing out his mouth like the last bit of ketchup out of a

bottle. Now, let's jump ahead to just after Spock's spacewalk into the

heart of V'Ger, when he ends up in Sick Bay. Clasping Kirk's hand, he says: "I saw

V'Ger's planet, a planet populated by living machines. Unbelievable

technology. V'Ger has knowledge that spans this universe. And, yet, with

all this pure logic, V'Ger is barren, cold, no mystery, no beauty. I

should have known [...] This simple feeling [clasping Kirk's hand] is beyond V'Ger's comprehension. No meaning, no hope, and, Jim, no answers. 'Is this all I am? Is there nothing more?'"

Spock is obviously dismayed by this lack of beauty and mystery and the

simple act of clasping a hand. The question is, why? The obvious answer

is that it's Spock's human half that's dismayed. And that his human half

is probably equally dismayed at the push for pure logic on his own home

planet of Vulcan. I'm sure anywhere from 3% to 10% of you folks out

there--the statistics stubbornly refuse to stay put--can probably relate to a

biological urge at odds with societal norms. No, I'm not saying that Spock is gay--he gets it on quite readily with both Leila Kalomi (Jill Ireland) in "This Side of Paradise" and Zarabeth (a scantily clad Mariette Hartley) in "All Our Yesterdays", two episodes where his emotions, and possibly his libido, get the best of him--only that his paradoxical genetic makeup could give rise to a similar set of challenges. In that respect, kolinahr can even be seen as a kind of conversion therapy. Except Spock isn't just

dismayed but surprised that there's no beauty or mystery or

simple acts of hand clasping on V'Ger's planet. And that surprise makes

me think those things indeed must exist on Spock's own home world, albeit in

muted form, furthering my belief that Vulcans are really just a bunch of poseurs (as is true of any culture, be it a New Guinea tribe, the Middle East, or

the United States of America.) Vulcans aren't machines, they just wish they

were machines. With horrifying clarity, Spock has seen just what

would happen were that wish ever to come true. That's not to say

he's now ready to embrace the violence-ridden, angst-ridden,

heartbreak-ridden Earth Human lifestyle, and, in fact, he never does (There's GOT to be some other alternative, he's probably thinking.)The only real problem with Star Trek: The Motion Picture is it goes on too damn long. At 132 minutes, it's...let me check...it's a whole three minutes longer than the average blockbuster film made in the late '70s. Um, let me amend my first sentence. Star Trek: The Motion Picture SEEMS to go on too damn long. Though the themes may be complex, the actual plot is simple enough. The whole thing could have been told in under an hour, the length of a typical Star Trek episode. In fact, it WAS a Star Trek episode: "The Changeling" from the series second season. The Enterprise receives yet another distress signal (think by now they'd learn to ignore those things given all the trouble they cause) and arrives at a planet that should have a population of four billion but is now devoid of life. Here today, gone tomorrow. The culprit turns out to be a space probe named Nomad, sent from Earth a few centuries earlier. Nomad is much smaller than V'Ger, so much so that it can be beamed aboard the Enterprise. Otherwise, it very much resembles V'Ger. It's looking for its creator, and refers to people as "units". Spock mind-melds with the probe and finds, like V'Ger, it came into contact with another space object from a more technologically advanced society. The two somehow merged into one, and now feels it must exterminate anything that gets in the way of its stated goal. The similarities between "The Changeling" and Star Trek: The Motion Picture are so great, some fans have referred to the latter as Where Nomad Has Gone Before. The episode was written by John Meredyth Lucas, but Executive Producer Gene Roddenberry was obviously taken with the idea of a machine in search of its creator. He used the idea again in the TV movie The Questor Tapes (though that machine was much more agreeable toward human beings) and now made it the subject of the first feature film. However, "The Changeling" had a much different ending. Temporarily mistaking Kirk for its creator, it decides to help him out by eliminating such inefficiencies as Uhura's memory and a couple of security guards. Needless to say this was help Kirk did not need. The Enterprise captain points out the errors of Nomad's ways to it, and the machine decides to destroy itself, but not before Kirk manages to have it beamed back out into space, where it explodes. As I said in an earlier installment, ending an episode with a bang was the commercial way of solving that week's dilemma in Star Trek's second season. So it's odd, and refreshing, to discover that, even with all the money being spent, the feature film wasn't going to take the easy way out and have V'Ger similarly blown out of the sky. According to the onscreen credits, science-fiction author Alan Dean Foster, who had written a series of books based on the animated series, came up with the story, and a producer by the name of Harold Livingston wrote the teleplay. Note I didn't say screenplay. Originally this was meant to be the pilot for a new TV show, Star Trek: Phase Two. So maybe the promotion to feature filmdom allowed for greater consideration on how to end this thing. In Livingston's words:

"We had a marvelous antagonist, so omnipotent that for us to defeat it or even communicate with it, or have any kind of relationship with it, made the initial concept of the story false. Here's this gigantic machine that's a million years further advanced than we are. Now, how the hell can we possibly deal with this? On what level? As the story developed, everything worked until the very end. How do you resolve this thing? If humans can defeat this marvelous machine, it's really not so great, is it? Or if it really IS great, will we like those humans who do defeat it? SHOULD they defeat it? Who is the story's hero anyway? That was the problem. We experimented with all kinds of approaches...we didn't know what to do with the ending. We always ended up against a blank wall."

NASA to the rescue! The then-director of the agency had mused that mechanical forms of life were someday likely in an interview in Penthouse (a once-popular girlie magazine that in recent years has come close to going under thanks to that mechanical form of life known as the Internet.) And that became the ending to Star Trek: The Motion Picture as Decker, Ilia, and V'Ger become one. And a good ending it is, no matter how many extra minutes it takes to get there.

Though they went to the The Motion Picture in droves, Star Trek fans were divided on its merits, and, judging by the Users Reviews on the IMDb, they remain divided, some comparing it favorably to the TV version, others complaining it bears no resemblance whatsoever. What I think both sides overlook is that the individual episodes of the original series didn't always resemble each other. "Arena", for instance, is very different from "A Piece of the Action", and both were written by the same guy! Whatever its flaws, Star Trek: The Motion Picture deserves another look.

The execs at Paramount, however, had seen enough. Sure, Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a hit, in fact, the fifth biggest hit of 1979. But it had cost so much to make, there was barely enough money left over for those execs to refurbish their hot tubs or build additions onto their mansions. If there was going to be a sequel--and, of course, there was going to be a sequel, after all, it was the fifth biggest hit of 1979--then a change was in order.

Gene Roddenberry never owned the classic series he created. The original proprietor was Lucille Ball, who sold it and the rest of Desilu studios to neighboring Paramount Pictures during Star Trek's second season. After the show went off the air, Roddenberry tried to buy it off them, but the price was too high. Still, when it came time to make a movie, they let him produce the thing. Figured he knew what he was doing. Star Trek, Star Wars, as long as the kids liked it. Now the kids were falling asleep during this expensive piece of psychobabble. That's not what they asked for! Give the public what it needs, bread and circuses (action figure tie-ins would be nice, too.) Actually, Roddenberry was perfectly capable of giving them that. Remember, the artistic first Trek pilot, "The Cage" had been followed by the relatively lowbrow "Where No Man Has Gone Before". Yeah, well, he should have done it that way in the beginning, the execs probably thought. Roddenberry was, in William Shatner's words, "kicked upstairs". For the rest of the movie franchise's decade-long run, he would be "executive consultant", except no one ever consulted him.

Next: Hail the Conquering Hero